Everest’s North Face: The True Story of the Wilder Side

Everest’s North Face: The True Story of the Wilder Side

When you picture the north face of Mount Everest, what do you see? For most, it’s a vision of the 1924 Mallory and Irvine expedition, the “Chinese Ladder,” and the infamous “Green Boots.” But here is the climber’s secret: when most people say “the north face,” they are actually referring to the Northeast Ridge—the standard climbing route on the Tibetan side. They’re missing the real story.

The true North Face is the massive, sheer wall that dominates the Tibetan plateau, a 9,000-foot vertical world of shadow and rock. It is a place of legend, colder and more ruthless than its southern counterpart. The Tibetan side of Everest is steeped in a darker, more dramatic history, defined by epic mysteries and almost superhuman feats of mountaineering.

This definitive guide clarifies the confusion. We will explore the true North Face (the wall) versus the standard climbing route (the ridge). We will then break down the infamous Three Steps, cover the breaking 2025 news from the face, and analyze the single, non-negotiable danger that sets this side of the mountain in a class of its own.

The “Two Norths”: Why Most Climbers Get It Wrong

The single most important thing to understand about the north face of Mount Everest is that it’s not one climb, but two fundamentally different concepts. Competitors and news articles often get this wrong. We will set the record straight.

The Standard Route: The Northeast Ridge

This is the route 99% of climbers on the Tibetan side use. It’s the “standard route” established by the Chinese in 1960. When you read about the “Three Steps” or the “Chinese Ladder,” you are reading about the Northeast Ridge.

This route avoids the terrifyingly steep true face by following the long, exposed ridge that borders it. While still an immense undertaking, it is a (relative) path of least resistance to the summit.

Expert Insight: Clarifying the Routes

Think of a castle. The Northeast Ridge is like climbing the long, steep, narrow rampart up to the highest tower. The True North Face, by contrast, is attempting to scale the sheer, vertical castle wall itself. Both lead to the same top, but they represent entirely different levels of technical difficulty and philosophy.

The True North Face: The Hornbein & Great Couloirs

This is the actual, 9,000-foot sheer wall. This is the “climber’s climb,” a place of mountaineering legend. The true North Face is dominated by two massive, deep gullies, or couloirs:

- The Great Couloir (or Norton Couloir): A massive gully on the right side of the face. In 1924, Noel Norton pioneered a high traverse into it, a feat that was decades ahead of its time.

- The Hornbein Couloir: A narrower, steeper couloir on the left side of the face.

As noted by climbing journals like [External Link: Planetmountain.com], climbing these couloirs is an elite, technical, and often-fatal endeavor, worlds apart from the fixed ropes of the Northeast Ridge.

Legends of the Face: The Stories That Define the North

The history of the North is not just about summits; it’s about mystery, controversy, and raw human ambition.

1924: The Enduring Mystery of Mallory and Irvine

The North Face will forever be synonymous with George Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine. Their 1924 British expedition was a story of tweed jackets, primitive oxygen gear, and a pure, romantic drive. Mallory’s famous reply to why he wanted to climb Everest—”Because it’s there”—was in reference to this very mountain.

They were last seen on June 8, 1924, “going strong for the top,” high on the Northeast Ridge. They vanished into the clouds, leaving the world with mountaineering’s greatest mystery: Did they summit?

In 1999, the “Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition” made a stunning discovery. They found George Mallory’s remarkably preserved body at 26,760 feet (8,157m) on the North Face. He was found with a severe rope-jerk injury around his waist, suggesting a fall. The camera that might have held the answer was not with him.

1960: The Controversial First Ascent by the Chinese

The first confirmed summit from the north side was achieved on May 25, 1960. A Chinese team, in a feat of incredible endurance and national pride, pushed up the Northeast Ridge. They claimed to have scaled the vertical rock face of the Second Step in the dark, a feat that Western climbers, for years, declared impossible.

Their claim was met with skepticism, primarily due to a lack of a summit photo. However, the expedition’s detailed reports and the physical evidence left behind (including the “Chinese Ladder” they would later install) have led most in the climbing world to accept their summit as legitimate.

1980: Reinhold Messner’s “Impossible” Solo Ascent

While Mallory defines the mystery of the North, Reinhold Messner defines its mastery. This is a story often missed by mainstream articles but is crucial to understanding the true North Face.

In 1980, Messner did the unthinkable. He climbed the mountain alone, in the post-monsoon season, with no supplemental oxygen, and via a new, more direct route on the North Face. After his climbing partner fell ill, Messner simply set off from Advanced Base Camp at 21,300 feet and, in a 3-day superhuman push, summited. He described the experience as a desperate, oxygen-starved, out-of-body struggle. It remains one of the purest and most staggering feats in mountaineering history.

2025 BREAKING NEWS: The First-Ever Ski Descent of the Hornbein Couloir

On October 7, 2025, the North Face became the stage for a new, mind-bending “first.” As reported by the [External Link: Associated Press] and [External Link: National Geographic], American ski-mountaineer Jim Morrison completed the first-ever ski descent of the Hornbein Couloir.

This is the single biggest event on the North Face in decades. The Hornbein Couloir is one of the steepest, most-feared features on the mountain. Morrison, filmed by legendary climber and director Jimmy Chin, skied down the “dream line” in a 10-hour, high-stakes descent from just below the summit. This 2025 achievement opens a new chapter, proving that even after a century, the North Face is still the ultimate canvas for pioneers.

The Climb: A Step-by-Step Guide Up the Northeast Ridge

For the 99% who attempt the standard route, the climb is a grueling, multi-week siege. This is what the journey feels like, from the high plateau to the roof of the world.

The Journey In: From Lhasa to Rongbuk Glacier

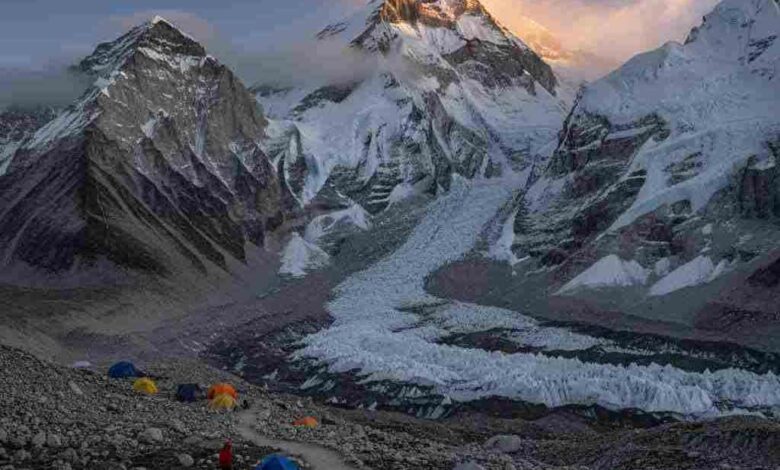

Unlike the 45-minute helicopter flight to the Nepali South Side Base Camp, the North Side requires a 1-2 week overland journey. Climbers first fly to Lhasa, Tibet (11,400 ft) to acclimatize. From there, it’s a multi-day drive in 4x4s across the vast, high-altitude Tibetan plateau to the Rongbuk Glacier. This long, slow approach is mandatory and helps the body adapt to the altitude.

Base Camp (17,000 ft) vs. Advanced Base Camp (21,300 ft)

The first stop, Chinese Base Camp, is a drive-up location at 17,000 feet. But this is not the real base of operations. The true climb begins at Advanced Base Camp (ABC), located at a staggering 21,300 feet (6,500m).

Reaching ABC is a 12-mile trek up the moraine of the Rongbuk Glacier. It’s a barren, wind-scoured moonscape of rock and ice. Teams will spend weeks here, making “rotations” up to the higher camps to acclimatize, before a human body can even survive a summit attempt.

The High Camps: The North Col (Camp 1) and Beyond

From ABC, the technical climb begins.

- Camp 1 (North Col): Climbers first ascend a steep, 2,000-foot ice wall to reach the North Col, a wide saddle at 23,000 feet (7,000m). This is Camp 1.

- Camp 2: From the Col, climbers ascend a long, gradual snow ridge, exposed to the brutal jet stream winds. Camp 2 is a desolate, rocky slab at 25,600 feet (7,800m).

- Camp 3: This is the final “launchpad.” A tiny platform on a steep, rocky face at 27,200 feet (8,300m), well inside the ‘Death Zone.’ Climbers arrive here on oxygen, force down fluids, and try to rest for a few hours before the final push.

Summit Day: The 1 AM Start

The summit attempt begins in the absolute blackness of 1 AM. It is a desperate, 10-18 hour battle against time, altitude, and cold. Climbers move as a “headlamp train,” a string of small lights ascending the rock. The goal is to reach the summit and get back down before their life-sustaining bottled oxygen runs out.

The Crux at 28,000 Feet: Navigating The Three Steps

Summit day on the North Side is defined by three technical rock-climbing sections known as the Three Steps. This is the route’s technical crux, all at an altitude where a human body is actively dying.

1. The First Step (8,500m / 27,890 ft)

The first obstacle is a large, boulder-like scramble. In the dark, at altitude, it’s a significant test of a climber’s energy. It’s the “warm-up” for what’s to come.

2. The Second Step & The “Chinese Ladder” (8,600m / 28,215 ft)

This is the most famous feature of the climb. It is a 100-foot (30m) vertical rock face. The 1960 Chinese team scaled this, but the 1975 Chinese expedition installed a 15-foot ladder on the final, steepest section. This ladder is still there today.

Expert Insight: The Ladder Doesn’t Make it “Easy”

Many assume the “Chinese Ladder” makes the Second Step simple. This is dangerously false. The ladder only bypasses the hardest 15 feet of a 100-foot-high obstacle. At 28,200 feet, wearing bulky boots and a thick down suit, just pulling your own body weight up a ladder is a desperate, lung-searing battle that can take 30 minutes.

3. The Third Step (8,700m / 28,540 ft)

A final, shorter rock step. While easier than the Second, its arrival is a psychological blow to exhausted climbers. But once past it, the route to the summit pyramid opens up.

The Summit Pyramid & The “Green Boots” Landmark

After the Third Step, climbers traverse a steep snow slope to the summit pyramid. This is where, for over 20 years, they would pass the most somber landmark on the mountain: “Green Boots.”

The body, believed to be Tsewang Paljor (an Indian climber who perished in the 1996 blizzard), lay in a small rock cave, his bright green boots a stark reminder of the route’s unforgiving nature. (His body has reportedly been moved in recent years). This final, long traverse leads to the narrow, corniced summit ridge and, finally, the roof of the world.

North Side vs. South Side: Which is Truly Harder?

This is the classic mountaineering debate. The answer is not simple. It’s a trade-off of different dangers.

Weather: The Unforgiving Jet Stream

Winner: South. The North Side is significantly colder and windier. It is fully exposed to the jet stream, which rips across the face. The cold is a dry, bone-penetrating cold that causes frostbite in minutes. The South Side, partially shielded by the Lhotse face, is relatively more protected.

Technicality: Three Steps vs. Khumbu Icefall

Winner: South (is less technical). The North Side is technically harder. It requires rock climbing skills at extreme altitude (The Three Steps). The South Side’s main danger is the Khumbu Icefall, a 2,000-foot river of shifting, collapsing ice. The Icefall isn’t “technical” climbing, but it is a game of Russian roulette, an objective hazard that kills climbers randomly.

Cost & Logistics: 2025-2026 Permit Breakdown

The China Mountaineering Association (CMA) controls all permits for the north side. According to data from respected Everest chronicler Alan Arnette, the North is often (but not always) slightly cheaper.

- North Side (Tibet): An all-in permit and logistics package for 2025-2026 runs between $45,000 – $80,000.

- South Side (Nepal): A similar package runs $50,000 – $100,000+. The Nepali government permit alone recently increased to $15,000 for 2025.

The Hard Truth: The “No Helicopter Rescue” Policy

This is the single most important difference. This is the “E-E-A-T” (Experience, Expertise) fact that defines the North.

The Hard Truth: On the North, You Are Your Own Rescuer

On the South Side (Nepal), helicopters can and do fly to Camp 2 (21,000 ft) to rescue climbers. A broken leg, severe HAPE, or HACE can be evacuated.

On the North Side (Tibet), this is not an option. The Chinese government has a strict no-helicopter-rescue policy in the high-altitude zones. The highest point of evacuation is Base Camp. If you get into trouble at ABC or any of the high camps, you must be carried down by your own team and yaks.

A broken leg at 25,000 feet, which might be survivable on the South Col, is often a death sentence from the North.

The North Face: A Test of Purity and Self-Reliance

The north face of Mount Everest, in all its forms, remains the mountain’s “wilder” side.

Whether it’s the standard Northeast Ridge—with its brutal cold, technical steps, and stark history—or the sheer, “true” face being skied by modern legends, the Tibetan side demands more. It is a colder, more logistically complex, and arguably purer challenge.

The South Side tests your endurance and your luck against objective danger. The North Side, with its raw exposure and absolute lack of high-altitude rescue, is a brutal test of your body’s limits and your team’s total self-reliance.

Are you planning an expedition or simply fascinated by the pioneers of mountaineering? [Internal Link: Explore our full guide to the 2025-2026 climbing seasons].

FAQs

Is the north face of Everest harder than the south?

It is considered technically harder due to the rock climbing (The Three Steps) at high altitude. It is also colder and windier. The primary danger, however, is the “no helicopter rescue” policy, which makes any emergency far more serious than on the South Side.

Has anyone climbed the true north face of Everest?

Yes. While most climbers use the Northeast Ridge, the true face has been climbed via routes like the Hornbein and Great Couloirs. The most famous ascent was Reinhold Messner’s 1980 solo climb, and the most recent major event was the 2025 first-ever ski descent of the Hornbein Couloir.

Who was “Green Boots” on Everest?

“Green Boots” is the name given to the body of a climber in a small rock alcove on the Northeast Ridge. He is widely believed to be Tsewang Paljor, an Indian climber who perished in the 1996 blizzard. His body, in bright green climbing boots, served as a grim landmark for over 20 years.

How much does it cost to climb Everest from the north side?

For the 2025-2026 seasons, you can expect an all-inclusive expedition (permits, logistics, guides, oxygen) to cost between $45,000 and $80,000, depending on the outfitter. This is managed through the China Mountaineering Association (CMA).

What are the Three Steps on Everest’s north face?

The Three Steps are three vertical-to-steep rock sections on the standard Northeast Ridge route, all above 27,800 feet. The First Step is a large boulder, the Second Step is a 100-foot vertical face (partially aided by a 15-foot ladder), and the Third Step is a final, shorter rock hurdle.

Why did China close the north side of Everest?

China closed the north side from 2020 through 2023 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They reopened the mountain for the 2024 climbing season and it remains open for 2025 and 2026, though with strict permit regulations.

What happened to Mallory and Irvine?

George Mallory and Andrew Irvine were last seen on June 8, 1924, ascending the Northeast Ridge. They disappeared and never returned. Mallory’s body was found in 1999, but Irvine’s body and, more importantly, their camera, have never been recovered. It remains the greatest mystery in mountaineering.

Can you see the north face from base camp?

Yes. The view of the true North Face from the Tibetan Base Camp (Rongbuk) is one of the most magnificent and intimidating mountain views on Earth, with the entire 9,000-foot sheer wall visible.